For the chronological story, begin your reading of John Donne’s poems at the bottom of the page. A facsimile edition of Donne’s Poems (1633) is now available on line.

Poem 10

John Donne’s “The Ecstasy” is a serious analysis of the mystery of love, resulting in the conclusion that “Love’s mysteries in souls do grow, But yet the body is his book.” For the poet, Platonic love–a ladder leading from physical to spiritual coupling–is far from platonic in its simplified meaning of “sexless”. En route, Donne manages to allude to medicine, alchemy, metaphysics, cosmology, scholasticism, and a score of other things. This is another poem that we like to think was addressed to Ann More. I’ve left out eleven stanzas in the centre of the poem, but hope you’ll read the the full poem.

The Ecstasy (excerpt)

Where, like a pillow on a bed,

A pregnant bank swelled up, to rest

The violet’s reclining head,

Sat we two, one another’s best.

Our hands were firmly cemented

With a fast balm, which thence did spring,

Our eye-beams twisted, and did thread

Our eyes upon one double string;

So to intergraft our hands, as yet

Was all our means to make us one,

And pictures in our eyes to get

Was all our propagation.

As ‘twixt two equal armies, Fate

Suspends uncertain victory,

Our souls (which to advance their state,

Were gone out) hung ‘twixt her and me.

…………

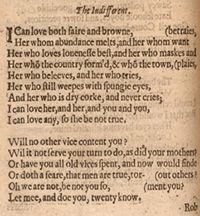

“The Indifferent” as printed in Poems by John Donne, 1633

As our blood labours to beget

Spirits, as like souls as it can,

Because such fingers need to knit

That subtle knot, which makes us man:

So must pure lovers’ souls descend

To affections, and to faculties,

Which sense may reach and apprehend,

Else a great prince in prison lies.

To our bodies turn we then, that so

Weak men on love revealed may look;

Love’s mysteries in souls do grow,

But yet the body is his book.

And if some lover, such as we,

Have heard this dialogue of one,

Let him still mark us, he shall see

Small change when we’re to bodies gone.

Poem 9

“The Good-Morrow” is another exquisite lyric that we like to think John Donne wrote for Ann More. As in “The Sun Rising,” their bed is the centre of the universe–an “everywhere.” Now the poet goes even further, saying that they (the lovers) are the two hemispheres of a world more significant than those that sea voyagers were discovering at the turn of the 17th century. This conceit is replete with sexual innuendo. The idea of the “waking souls” and lovers lying so close that their eyes are locked together is taken further in “The Ecstasy” above.

The Good-Morrow

I wonder by my troth, what thou and I

Did, till we loved? were we not weaned till then,

But sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the seven sleepers’ den?

‘Twas so; but this, all pleasures fancies be.

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, ’twas but a dream of thee.

And now good-morrow to our waking souls,

Which watch not one another out of fear.

For love all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone,

Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown,

Let us possess one world; each hath one, and is one.

My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears,

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest.

Where can we find two better hemispheres

Without sharp north, without declining west?

Whatever dies, was not mixed equally;

If our two loves be one, or thou and I

Love so alike that none do slacken, none can die.

Poem 8

In John Donne’s “The Canonization”, the two lovers die and are canonized–made saints–because of the intensity of their love. The poet puns on the word “die”, which also meant orgasm, “la petite mort” in French. It’s the sort of phrase Donne liked to coin, but Shakespeare got there before him. In Much Ado About Nothing, Benedick teases Beatrice, “I will live in thy heart, die in thy lap, and be buried in thy eyes”. This didn’t stop Donne from using the pun in many of his love poems, as indeed did many 16th and 17th-century poets..

The Canonization

For God’s sake hold your tongue and let me love,

Or chide my palsy, or my gout,

My five gray hairs, or ruin’d fortune flout,

With wealth your state, your mind with arts improve,

Take you a course, get you a place,

Observe his Honour, or his Grace,

Or the King’s real, or his stamped face

Contemplate ; what you will, approve,

So you will let me love.

Alas, alas, who’s injured by my love?

What merchant’s ships have my sighs drowned?

Who says my tears have overflowed his ground?

When did my colds a forward spring remove?

When did the heats which my veins fill

Add one more to the plaguy bill?

Soldiers find wars, and lawyers find out still

Litigious men, which quarrels move,

Though she and I do love.

Call us what you will, we are made such by love.

Call her one, me another fly,

We are tapers too, and at our own cost die,

And we in us find the eagle and the dove.

The phoenix riddle hath more wit

By us ; we two being one, are it.

So to one neutral thing both sexes fit.

We die and rise the same, and prove

Mysterious by this love.

We can die by it, if not live by love,

And if unfit for tomb or hearse

Our legend be, it will be fit for verse;

And if no piece of chronicle we prove,

We’ll build in sonnets pretty rooms.

As well a well-wrought urn becomes

The greatest ashes, as half-acre tombs,

And by these hymns, all shall approve

Us canonized for love:

And thus invoke us, “You whom reverend love

Made one another’s hermitage;

You, to whom love was peace, that now is rage;

Who did the whole world’s soul contract, and drove

Into the glasses of your eyes

(So made such mirrors, and such spies,

That they did all to you epitomize)

Countries, towns, courts: beg from above

A pattern of your love!”

Poem 7

Now is the time of year when students write essays about John Donne’s poems. Popular choices are “The Sun Rising” and “The Canonization” (above), two lyrics that Donne probably wrote for Ann More in the early years of their marriage. In both, the lovers engage in extravagant acts of love and cloister themselves in bed, rejecting the demands of the world. They were most likely written after King James came to the throne in 1603 since “The Sun Rising” refers directly to the King and “The Canonization” alludes to a coin stamped with the King’s face.

The Sun Rising

Busy old fool, unruly sun,

Why dost thou thus,

Through windows, and through curtains call on us?

Must to thy motions lovers’ seasons run?

Saucy pedantic wretch, go chide

Late school-boys, and sour prentices,

Go tell court-huntsmen that the King will ride,

Call country ants to harvest offices.

Love, all alike, no season knows, nor clime,

Nor hours, days, months, which are the rags of time.

Thy beams, so reverend and strong

Why shouldst thou think?

I could eclipse and cloud them with a wink,

But that I would not lose her sight so long:

If her eyes have not blinded thine,

Look, and tomorrow late, tell me,

Whether both th’Indias of spice and mine

Be where thou left’st them, or lie here with me.

Ask for those kings whom thou saw’st yesterday,

And thou shalt hear, All here in one bed lay.

She is all states, and all princes, I,

Nothing else is.

Princes do but play us; compared to this,

All honour’s mimic; all wealth alchemy.

Thou sun art half as happy as we,

In that the world’s contracted thus;

Thine age asks ease, and since thy duties be

To warm the world, that’s done in warming us.

Shine here to us and thou art everywhere.

This bed thy centre is, these walls, thy sphere.

Poem 6

It’s bad enough to suffer the chills and fevers of unrequited love. Even worse to whine about it in poetry. Although the lover’s grief is tamed by rhyme and meter, he is triply shamed when someone sets the verses to music. A number of John Donne’s poems were made into songs in his own time and perhaps he hoped that this lyric, which has a bit of a Nashville twang to it, might make the country music hall of fame.

The Triple Fool

I am two fools, I know,

For loving, and for saying so

In whining poetry.

But where’s that wiseman, that would not be I,

If she would not deny?

Then as th’earth’s inward narrow crooked lanes

Do purge sea water’s fretful salt away,

I thought, if I could draw my pains

Through rhyme’s vexation, I should them allay.

Grief brought to numbers cannot be so fierce,

For, he tames it, that fetters it in verse.

But when I have done so,

Some man, his art and voice to show,

Doth set and sing my pain,

And, by delighting many, frees again

Grief, which verse did restrain.

To love and grief tribute of verse belongs,

But not of such as pleases when ’tis read,

Both are increased by such songs:

For both their triumphs so are published,

And I, which was two fools, do so grow three.

Who are a little wise, the best fools be.

Poem 5

“The Flea” is a clever seduction poem that twists logic to convince a woman (surely not the well-bred teenager, Ann More?) that, since the flea has already bitten them both, and thus mingled their blood, there’s no reason to fend off the poet’s advances. Ribald poems about a flea exploring a woman’s body were “a smutty old joke”, though John Donne’s is surely the most exquisite written on this theme.

The Flea

Mark but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deny’st me is.

Me it sucked first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea, our two bloods mingled be.

Confess it, this cannot be said

A sin, or shame, or loss of maidenhead,

Yet this enjoys before it woo,

And pampered swells with one blood made of two,

And this, alas, is more than we would do.

Oh stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where we almost, nay more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is.

Though parents grudge, and you, we are met,

And cloistered in these living walls of jet.

Though use make you apt to kill me,

Let not to this, self murder added be,

And sacrilege, three sins in killing three.

Cruel and sudden, hast thou since

Purpled thy nail, in blood of innocence?

In what could this flea guilty be,

Except in that drop which it sucked from thee?

Yet thou triumph’st, and say’st that thou

Find’st not thyself, nor me the weaker now.

‘Tis true, then learn how false, fears be.

Just so much honour, when thou yield’st to me,

Will waste, as this flea’s death took life from thee.

Poem 4

Some of the poems in John Donne’s Songs and Sonnets are variations on Elizabethan themes, such as the cold, inconstant mistress. As a law student, would-be courtier, and later secretary to Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Keeper, Donne favoured witty, cerebral poems, but at some point he began to write the more mature love poems we associate with Ann More. But which poems were written for Ann and which for other women? With few exceptions, nobody knows. However some of the Songs and Sonnets, like the one below, play around with the word “more”, suggesting that these poems had found a new audience.

A Valediction: of Weeping

Let me pour forth

My tears before thy face, whilst I stay here,

For thy face coins them, and thy stamp they bear,

And by this mintage they are something worth,

For thus they be

Pregnant of thee.

Fruits of much grief they are, emblems of more,

When a tear falls, that thou falls which it bore,

So thou and I are nothing then, when on a divers shore.

On a round ball

A workman that hath copies by, can lay

An Europe, Afric, and an Asia,

And quickly make that, which was nothing, all,

So doth each tear,

Which thee doth wear,

A globe, yea world by that impression grow,

Till thy tears mixed with mine do overflow

This world, by waters sent from thee, my heaven dissolved so.

O more than moon,

Draw not up seas to drown me in thy sphere,

Weep me not dead, in thine arms, but forbear

To teach the sea, what it may do too soon.

Let not the wind

Example find,

To do me more harm, than it purposeth.

Since thou and I sigh one another’s breath,

Whoe’er sighs most is cruellest, and hastes the other’s death.

Poem 3

As well as the Songs and Sonnets, John Donne also wrote verse letters, epigrams, satires, and elegies that circulated in manuscript amongst his male friends. Five of the elegies (including the one below) were refused a license when Donne’s poems were printed after his death, and the most licentious, “The Comparison”, still seldom finds its way into print. Although most were written before he met Ann More in 1599, it’s tempting to read Ann into some of the elegies, particularly the dazzling seduction poem below in which a woman well above the poet’s social station is stripped of her jewels and rich clothing, piece by leisurely piece.

To his Mistress Going to Bed

Come, madam, come, all rest my powers defy,

Until I labour, I in labour lie.

The foe oft-times, having the foe in sight,

Is tired with standing, though they never fight.

Off with that girdle, like heaven’s zone glistering,

But a far fairer world encompassing.

Unpin that spangled breast-plate, which you wear,

That th’ eyes of busy fools may be stopped there.

Unlace yourself, for that harmonious chime

Tells me from you that now ‘tis your bed-time.

Off with that happy busk, which I envy,

That still can be, and still can stand so nigh.

Your gown going off, such beauteous state reveals,

As when from flowery meads th’ hill’s shadow steals.

Off with your wiry coronet, and show

The hairy diadem which on you doth grow.

Now off with those shoes, then safely tread

In this love’s hallowed temple, this soft bed.

In such white robes heaven’s angels used to be

Revealed by men; thou angel bring’st with thee

A heaven like Mahomet’s paradise; and though

Ill spirits walk in white, we easily know

By this these angels from an evil sprite,

Those set our hairs, but these our flesh upright.

Licence my roving hands, and let them go

Before, behind, between, above, below.

O my America, my new found land,

My kingdom, safest when with one man manned,

My mine of precious stones, my empery,

How am I blest in thus discovering thee!

To enter in these bonds, is to be free;

Then where my hand is set, my seal shall be.

Full nakedness, all joys are due to thee.

As souls unbodied, bodies unclothed must be

To taste whole joys. Gems which you women use

Are like Atlanta’s balls, cast in men’s views,

That when a fool’s eye lighteth on a gem,

His earthly soul may covet theirs, not them.

Like pictures, or like books’ gay coverings made

For laymen, are all women thus arrayed.

Themselves are mystic books, which only we

Whom their imputed grace will dignify

Must see revealed. Then since I may know,

As liberally as to thy midwife show

Thyself: cast all, yea, this white linen hence,

Here is no penance, much less innocence.

To teach thee, I am naked first, why then

What needst thou have more covering than a man.

Poem 2

Here’s a poem from John Donne’s Songs and Sonnets that dramatizes the conflict between a woman and the young man who is “killed” by her frigid scorn. His ghost, he threatens, will sneak into her bedchamber and discover her in another’s arms, begging for satisfaction. Or is that really what it’s about? “Cold quicksilver sweat” might also suggest the mercury that was rubbed on skin to treat syphilis, a cure as punishing as the disease. Even given poetic hyperbole, this is a scarily vindictive poem–a good one to spook a past lover with at Hallowe’en.

The Apparition

When by the scorn, O murderess, I am dead,

And that thou think’st thee free

From all solicitation from me,

Then shall my ghost come to thy bed,

And thee, feigned vestal, in worse arms shall see.

Then thy sick taper will begin to wink,

And he, whose thou art then, being tired before,

Will if thou stir, or pinch to wake him, think

Thou call’st for more,

And in false sleep will from thee shrink,

And then poor aspen wretch, neglected thou,

Bathed in a cold quicksilver sweat wilt lie

A verier ghost than I.

What I will say, I will not tell thee now,

Lest that preserve thee; and since my love is spent,

I had rather thou shouldst painfully repent,

Than by my threatenings rest still innocent.

Poem 1

I’ll start things off by posting some of John Donne’s remarkable Songs and Sonnets. Although we don’t know the chronology of these clever love poems, the libertine posturing in “The Indifferent” suggests that it was written when he was a law student and young-man-about-town. This was long before he married Ann More in December 1601. When I read these cocky verses, I wonder whether Donne really had as many mistresses as he claims, or whether he was simply writing fiction like the rest of us.

The Indifferent

I can love both fair and brown,

Her whom abundance melts and her whom want betrays,

Her who loves loneness best and her who masks and plays,

Her whom the country formed and whom the town,

Her who believes and her who tries,

Her who still weeps with spongy eyes,

And her who is dry cork and never cries;

I can love her, and her, and you and you,

I can love any, so she be not true.

Will no other vice content you?

Will it not serve your turn to do, as did your mothers?

Have you old vices spent, and now would find out others?

Or doth a fear, that men are true, torment you?

Oh we are not, be not you so,

Let me, and do you, twenty know.

Rob me, but bind me not, and let me go.

Must I, who came to travail through you,

Grow your fixed subject, because you are true?

Venus heard me sigh this song,

And by love’s sweetest part, variety, she swore,

She heard not this till now, and that it should be so no more.

She went, examined, and returned ere long,

And said, ‘Alas, some two or three

Poor heretics in love there be,

Which think to establish dangerous constancy.

But I have told them, “Since you will be true,

You shall be true to them, who are false to you.”‘