The inspiration behind my novel Muse is the amazing town of Avignon in France, where the popes resided in the 14th century. I visited it five times to explore the popes’ palace, the city wall, the rivers and canals, and the surviving medieval streets and buildings. I went there to soak up the atmosphere and walk in Solange’s shoes. The late middle ages are so far back in time that facts are scarce and history blurs into poetry and myth. This made the city even more attractive to me, because I could gather many story-strands into a single character, the fictional Solange Le Blanc.

The inspiration behind my novel Muse is the amazing town of Avignon in France, where the popes resided in the 14th century. I visited it five times to explore the popes’ palace, the city wall, the rivers and canals, and the surviving medieval streets and buildings. I went there to soak up the atmosphere and walk in Solange’s shoes. The late middle ages are so far back in time that facts are scarce and history blurs into poetry and myth. This made the city even more attractive to me, because I could gather many story-strands into a single character, the fictional Solange Le Blanc.

Early on, I decided to tell the story from Solange’s point of view. This was a blessing, because it would have been drudgery to wade through the piles of information about theAvignon popes. Acres of worm-eaten parchment sit in the Vaucluse archives, not to mention the Vatican archives in Rome.

Early on, I decided to tell the story from Solange’s point of view. This was a blessing, because it would have been drudgery to wade through the piles of information about theAvignon popes. Acres of worm-eaten parchment sit in the Vaucluse archives, not to mention the Vatican archives in Rome.

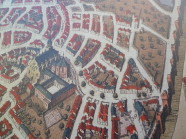

The municipal archives were less intimidating and it was there I sought out medieval maps of Avignon. No two maps put the streets in the same place or called them by the same names. I knew that the Italian poet Francesco Petrarch had lived in the city and fathered two children, so I asked the archivist for birth records. He informed me, sadly, that the records only stretched back to 1500. Far from being disappointed, I felt liberated, because I was free to make Solange the children’s mother.

Because the biographies of Petrarch seldom agreed, I could cherry-pick the ripest facts. He wrote love poems to Laura, whose identity is still a mystery. Was she the married noblewoman Laura de Sade (née de Noves)? Petrarch recorded their meeting, the famed innamoramento, but fudged the date to make it more poetic. Myths have obscured the story from that point forward. Although real, Laura became so removed from fact that she became a legend, like Lady Diana.

Medieval thinking was far from logical. If you crack open a copy of The Golden Legend, you’ll realize that most of the book is preposterous. Even the Avignon popes and cardinals were superstitious and believed in miracles. People accused of sorcery were tortured in horrific ways. This was the sort of information, like the city’s filth and stench, which could swamp the story. To allow readers to suspend their disbelief and empathize with Solange,Muse could not be wedded to the facts. I had to be selective.

This brings up the thorny issue of whether novelists are  required to stick to the truth or whether saying it’s fiction is a license to play around with the facts. I try not to cross swords with history since it’s a lot bigger than me. Luckily, most of Muse doesn’t deal with historically-recorded events, but more intimate matters, such as what people said and thought, and whose beds they crawled into in their private hours. This gave me latitude to use the facts that worked, to avoid the ones that didn’t, and to invent a great deal. As Michael Ondaatje said, “Facts breed and what they produce is fiction.”

required to stick to the truth or whether saying it’s fiction is a license to play around with the facts. I try not to cross swords with history since it’s a lot bigger than me. Luckily, most of Muse doesn’t deal with historically-recorded events, but more intimate matters, such as what people said and thought, and whose beds they crawled into in their private hours. This gave me latitude to use the facts that worked, to avoid the ones that didn’t, and to invent a great deal. As Michael Ondaatje said, “Facts breed and what they produce is fiction.”

Since Solange was fictional, I could invent freely without flying in the face of known facts. I learned to trust my inner historian, since I’ve read widely in medieval authors like Petrarch, Chaucer, Dante, and Boccaccio. A few times, I got into a sweat dovetailing the dates of Petrarch and Pope Clement VI, but having a fictional heroine gave me wiggle room. I was following Petrarch’s lead, since he once told a friend, “If true facts are lacking, add imaginary ones. Invention in the service of truth is not lying.”

I tried to find a balance between fact and fiction, to create verisimilitude while harnessing the emotional power of fiction. The Globe and Mail review of Muse sums up nicely, “The use of fictional characters interacting with true historical figures is a liberating creative device and as long as the story is executed within the framework of reality, there is generally no expectation from the reader of exact historical veracity.”

When I had trouble writing, I looked at maps, drawings, poems, and letters for inspiration. I fed my muse, searching for quirky facts to inspire me, like the oddball discovery that one of the popes had ordered Petrarch (and his brother Gherardo) to send their sister to his chamber. This was one of the stray facts that opened a secret door in the popes’ palace. Don’t be surprised, when reading Muse, if a fictional person walks through that real door. After all, this is my 14th century, not history’s.

When I had trouble writing, I looked at maps, drawings, poems, and letters for inspiration. I fed my muse, searching for quirky facts to inspire me, like the oddball discovery that one of the popes had ordered Petrarch (and his brother Gherardo) to send their sister to his chamber. This was one of the stray facts that opened a secret door in the popes’ palace. Don’t be surprised, when reading Muse, if a fictional person walks through that real door. After all, this is my 14th century, not history’s.

This blog originally appeared at Cozy Up With A Good Read